CLV-Focused Discovery-Driven Planning for Customer-Centric Startups

Written by: Rodrigo Fernandes, CFO, Pingback and Daniel McCarthy, Co-founder, Theta | May 2023

It can be difficult for a startup business to formulate a strong view of the outlook and longer-term viability of its business. Data is highly limited at this stage of the company lifecycle; you don’t have the luxury of years of customer purchase and profitability history, for example. With all the inevitable uncertainties associated with companies in their infancy, there isn’t a perfect way to assess whether there is product-market fit (and if so, where). That being said, we believe that founders and executives can make great strides towards resolving these uncertainties by pursuing a bottom-up, customer lifetime value (CLV)-focused approach to “Discovery Driven Planning (DDP).”

DDP is similar to the framework espoused by best-selling authors/thought leaders Michael Mauboussin and Al Rappaport in their celebrated book, Expectations Investing (EI). The premise behind both DDP and EI is that you should start planning with your end goal/state in mind, and work backwards from there. While the concepts of DDP and EI are not new, we believe that it can be even more potent when viewed through a CLV lens.

The How-to-Do It

Instead of forecasting what revenue, units sold, and other profitability drivers will be over the next 6, 12, and 24 months, start your plan with your desired outcome. Traditionally, this is a certain level of revenue and/or profit. By taking these values as given and working backwards, you can more quickly identify the best way to get to your desired end state (e.g., how many units you will need to sell, at what price, with what associated cost).

Instead of forecasting what revenue, units sold, and other profitability drivers will be over the next 6, 12, and 24 months, start your plan with your desired outcome.

But it’s important to go one step further.

Overall profit is often the target outcome measure, but it should not be the starting point for most startups. It is just as important – perhaps more so – to work backward from outcome measures that revolve around long-term client-level profitability.

If you make money on the customers that you acquire in aggregate, you are likely more than halfway to creating a successful business. You also need to think about overhead expenses and the size of the market, among other factors. But none of these other things matter if, no matter how you cut it, you are “upside down” when you acquire a customer.

Using DDP, strive for a certain ratio of CLV relative to customer acquisition cost (CAC) as the main goal instead of (or at least in addition to) a certain value for revenue and profit. Before we can talk about this ratio though, we need to define what it is in the first place. CAC is the sum of all expenses related to customer acquisition divided by the number of acquired customers. CLV is the net present value of all variable profits and costs, including the CAC. This is, quite literally, the value of a customer. Post-acquisition value (PAV) is CLV before we deduct CAC.

Using DDP, strive for a certain ratio of CLV relative to customer acquisition cost (CAC) as the main goal instead of (or at least in addition to) a certain value for revenue and profit.

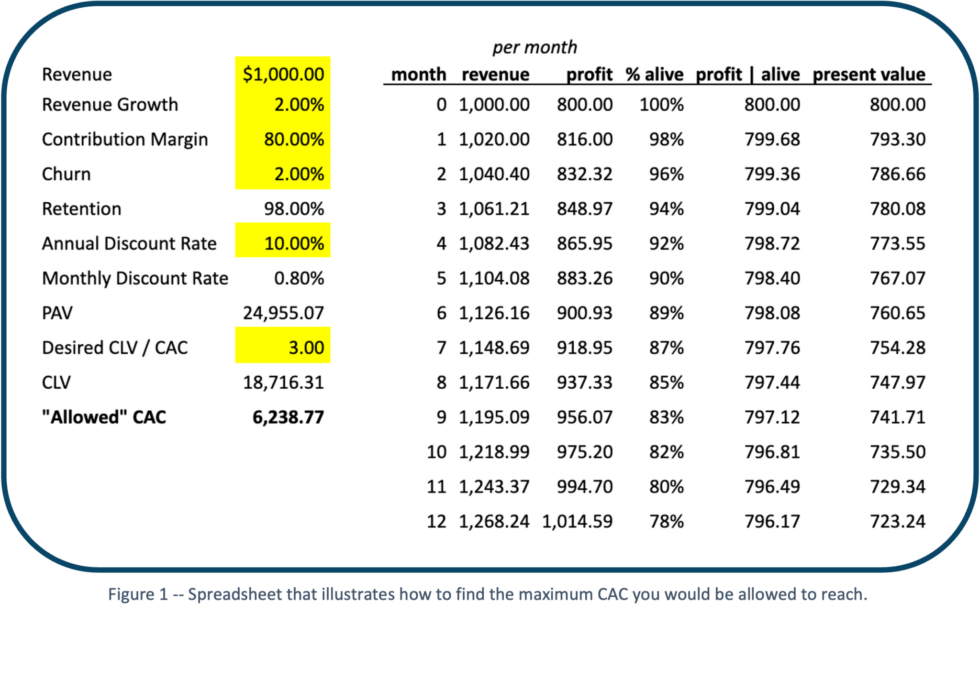

When calculating CLV in your early stage, you need to consider retention, the discount rate, and contribution profitability. What values are appropriate is going to be driven by some combination of whatever directly observed data has been generated from your company thus far to date and benchmarks from comparable companies.

This simple spreadsheet (figure 1) will guide you through the calculation. Be conservative in setting the drivers, especially the expected lifetime of your clients. It can be highly uncertain for very early-stage businesses. If healthy CLV projections are predicated upon overly optimistic projections of customer longevity, you may want to think hard about the viability of your business.

Now let’s think about the denominator of the CLV/CAC ratio. Investors often say that a good CLV/CAC ratio is above 3x. If we were to follow this rule, then if the CLV is $300, CAC should be $100 or less.

Of course, a good ratio depends on the business model of the company. Companies with small target markets and/or significant required overhead expenses need a higher CLV/CAC ratio to have a realistic path to profitability. Companies with sizeable target markets and/or can “run lean” may be able to get away with lower ratios in steady-state. Whatever the case is, the CLV/CAC ratio had better be meaningfully greater than zero.

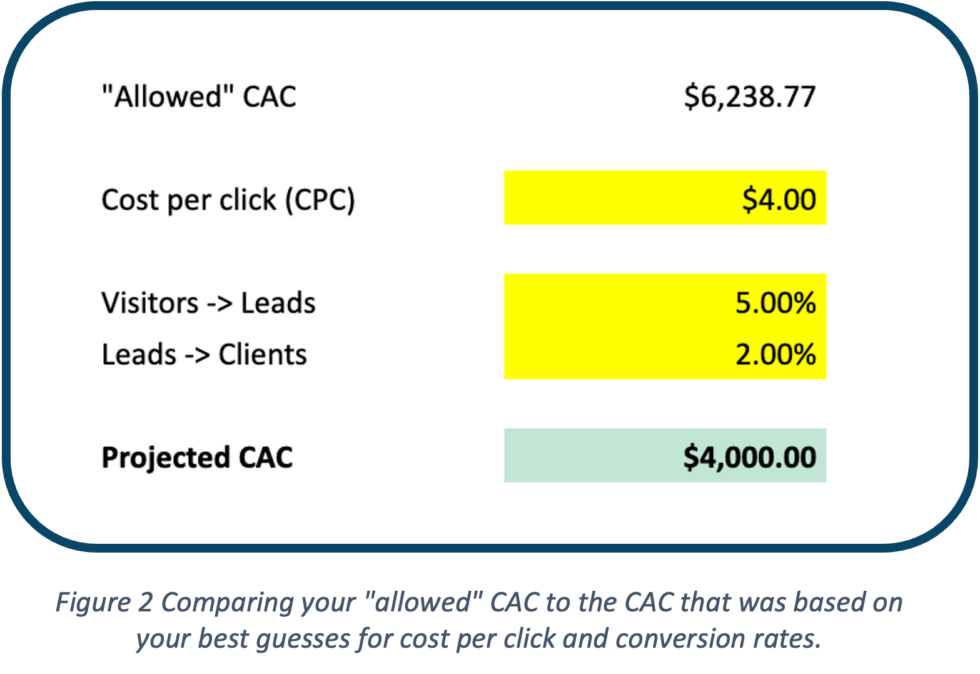

In the same way that CLV is driven off a collection of data, hypotheses, and assumptions, its counterpart CAC will be driven off (at least) a few assumptions, such as the cost to attract visitors to your website, the conversion rate of the visitors to leads, and the conversion rate of leads to clients (figure 2).

With your best assumptions for the above cost and ratios, you can check if the CAC that comes out on the other side is within the range it should be to generate your target CLV/CAC ratio.

Conclusion

Both the DDP and EI frameworks note and assume that the plans that you start with are not the plans that you end with; they are just version 1.0. You will need to run experiments and checkpoints to update the plans as new data comes in. But this approach is a strong, logically sound foundation upon which you can assess success against as you grow and build your business.

By focusing on target client-level profitability, you can more quickly determine whether there is a realistic path to profitability and chart out the best possible course to navigate towards it.

Thank you to Rodgrigo Fernades for his partnership in guest writing with us on this topic. He is the CFO of Pingback and a professor at Fundação Dom Cabral. According to Rodrigo, he has a background in Computer Science, but he ended up using computers mostly for writing and making financial models.